Couple of definitely shootable bucks, still in velvet, caught on one of friend Scott Morgan’s trail cams. Grandson Cody says he wants to hunt with me this year so it’s probably not too early to start doing a little long range planning.

Just One Of The Guys

This story from the September 2008 issue of Wildfowl Magazine was awarded 1st place in the 2009 Magazine Humor category of the OWAA Excellence In Craft Contest.

I first noticed a difference in Bob the day I rode with him in his pickup truck to a big sporting goods store to take advantage of a preseason sale. Bob had been an over-the-road trucker at one time and could handle anything from an eighteen-wheeler to the dinkiest subcompact, yet he seemed to be having trouble parallel parking. He backed and filled and backed and filled some more until finally he gave up and left the truck at a funny angle, quite a ways from the curb.

I didn’t think any more about it until one day, about a week into duck season, we were sitting in the blind, killing time and trying to decide whether to bail out or give it one more hour. It was one of those days when the ducks weren’t flying and about all there was to do was drink coffee, pet the dog, and shoot the breeze. I could tell something was on Bob’s mind.

“There’s something I have to tell you and the other guys”, he said.

I figured he was going to say he was changing jobs or maybe had a health problem.

“I’ve had an operation”, he said.

Naturally I’m thinking gall bladder, appendectomy, the usual stuff. I was totally unprepared for what came next.

“Oh?” I asked. “”You doing OK now?”

”Oh yeah,” he said, sipping his coffee. “I’m fine. But you don’t understand. I’ve had a…well… I’m not Bob any more. I’m Bobbi Sue.”

It didn’t hit me immediately, probably because I was in shock. “You mean….” I fumbled for the right words. “You’ve had one of those… those… whatchacallits?…”

“ You got it”, replied Bob. “ I’ve had a sex change operation. But I don’t want it to change anything as far as our duck hunting is concerned. I just want everybody to keep thinking of me as one of the guys. In fact, if you’d like, you can keep calling me Bob instead of Bobbi Sue.”

Well, let me tell you, it’s awfully hard to think of a guy who is 6’3”, weighs 240, and chews tobacco as Bobbi Sue.

“How is Alice taking this?” I asked. This had to be quite a shock to his wife.

“You mean Al?”

“Oh Lordy, no”, I muttered, with my head in my hands. I was starting to have trouble dealing with this.

“When I left the house she… I mean he, was lying on the couch drinking beer, belching, and watching NASCAR on TV”

Bob continued to hunt with our group all season and there were no major problems. He was a likeable guy and a good, safe hunter, which is about all we require in a hunting partner. But as the season wore on we began to notice a few subtle changes. Once, when we drove out-of-state for a guided duck hunt, we got lost and Bob cheerfully volunteered to go into a service station and ask directions.

Something else was different, too. The rest of us just sort of voluntarily started cleaning up our language when Bob was around. One morning when a flock of teal buzzed our decoys and I never even had time to get off a shot I found myself saying, “My goodness! Those little fellows are certainly fast, aren’t they.”

We noticed some other changes, too. When nature called, Bob started getting out of the blind and walking back to our trailer to use the bathroom. In fact he once drove all the way into town and back. And, when it was my turn, I started going as far away from the blind as possible and hiding behind a tree.

And later, after the hunt was over and the guns were put away, when the rest of us had a beer, Bob would sip a glass of white wine. Once he even asked for a Singapore Sling but nobody knew how to make one.

About once a month Bob got sort of cranky but we just overlooked it and tried to stay out of his way till he felt better. And you wouldn’t believe some of the things he started carrying in his blind bag.

So, aside from these minor changes, Bob is pretty much the same. He looks about like he always did, if you can ignore the occasional touch of lip-gloss and eye shadow. He still chews tobacco in the blind but he doesn’t spit the juice on the floor anymore, and I can’t remember him breaking wind once all season.

We’re already looking forward to September and teal season. It’ll probably be ninety degrees, sweat will be rolling off the rest of us, and the dogs’ tongues will be hanging out. Someone will look over at Bob and say, “Aren’t you sweating, Bob?” and he’ll say, “No, but I’m perspiring a little.”

l

No River For Old Men

This story was first published in the August 2009 issue of Wyoming Wildlife magazine. It was awarded the Best Magazine Humor award in the 2010 Magazine Humor contest of the Outdoor Writers Association of America Excellence In Craft Contests.

My buddy Ned was ecstatic. “Can you believe it? There’s nobody here but us!”

Ned had parked my truck at a campground. I had let him drive because the grandkids had taken my car keys away. They said I was just an accident waiting to happen. We had walked about a half mile downstream to a popular “honey hole”. It was usually crowded but today we seemed to have it all to ourselves.

Ned tweezered a #18 elk hair caddis out of his fly box and handed it to me.

“Can you tie this on for me?”, he asked, “ I can hardly see it.”

“Sorry”, I said. “I forgot my bifocals”. I thought I was wearing them but obviously I was not. I started wondering what I had done with them but couldn’t remember.

“Then how are we going to fish if neither of us can see how to tie on a fly?”

“We’ll just have to use bigger flies”, I explained. “Like maybe #8 hoppers. But it’s a mootpoint because we can’t fish here anyway”.Ned stared at me, stunned. “What do you mean, we can’t fish here?”

“Look, Ned….” I sat down on a log. My back was already starting to ach from the hike in.

“Like you said, Ned, there’s nobody here but us. We’re both seventy years old. What if we fall down and can’t get back up out of the water? What if we slip on a slick, moss-covered rock and go tumbling downstream? There’s nobody here to help us.”

Ned is dumb enough to hang around with me but he’s not totally brain dead yet.

“I never thought of it that way”, he said, rubbing the gray stubble on his chin. “I gotta admit you may have a point”.

“The only reason I agreed to walk all the way in here was because I thought there would be other people fishing here”, I told him. I could see by the look on his face that I was going to have to explain my theory in detail to him. “At our age we can’t just wade into the water and start flinging flies around like we did when we were twenty-five or thirty. Or even forty or fifty. First we need to find what I call a geezer-friendly venue.”

Ned leaned against a tree and stared longingly at the river where a few trout were sipping emergers in the surface film while I continued to expound on my theory.

“What if there’s a mixture of young guys and old guys?” asked Ned.

“That probably means it’s okay. But we should study the water carefully before we wade in. The old guys we see fishing may just be too dumb to realize they’re in danger. Age is no guarantee of wisdom.”

“But if we do decide to give it a try, we should fish upstream from the young guys so they can fish us out if we lose our balance and go floating downstream”, said Ned, warming to my theory.

“You catch on quick”, I said.

“What?” said Ned.

“I SAID “YOU CATCH ON QUICK”, I yelled. “Sit down here on the log beside me so you can hear what I’m saying…. Now where was I?

“You were explaining your theory to me”, said Ned. “Something about fishing where there are young guys around.”

“Oh yeah”, it was starting to come back to me now. “But having young guys around is no guarantee, because if the fishing is really hot – say there’s a terrific hatch on – the young guys may just keep fishing as we go floating by, gurgling and screaming. In fact they may get mad at us for putting the fish down, like we used to do when old guys went floating past us.”

I pulled my collapsible wading staff – which I now called my “ geezer stick” – from its holster on my belt and leaned against it to help me stand up. We started walking back toward the truck, then remembered the truck was in the opposite direction, so we turned around and walked the other way while I filled Ned in on some of the finer points of my theory.

“Those little pockets in your vest… don’t fill them all up with flies, tippet material, leaders, and other fishing stuff. Save some for pills, salves, suppositories, and any other meds that might come in handy on the stream.”

Ned nodded in agreement.

“And one other thing”, I added. “When you’re just smoking everybody else on the river and some young whipper-snapper asks you what you’re using, just say “Fifty years of experience, Sonny.”

When we got back to the truck I found my bifocals in the glove box, right where I had put them. I pulled out my river map and we started looking for a place on the river that would be suitably crowded for guys our age. In other words, a geezer-friendly venue. We’d head out right after our nap.

How we found Lost Lake

This story was published in Wyoming Wildlife magazine in March 2006.

It was 1970 and I was driving my new Bronco home from the dealership. My first four wheel drive! No longer would I be confined to the road, forced to fish where others fished. Now I could go ANYWHERE! Bear in mind this was before the SUV craze. Now, in the twenty-first century, it seems everyone has 4WD. But in 1970 if you wanted to fish any distance from a road you usually had to [gasp!] walk.

Our annual family vacation out west would be coming up soon. We always stayed for ten days at a “guest ranch” located on a state highway. Until now my father-in-law and I had done most of our fishing close to a black top road. In fact the highway paralleled the river for several miles. The roadside was public access but we had permission to fish the private water on the other side. But those little blue spots on the topo maps, high mountain lakes up where the elevation lines were close together, had always beckoned seductively to us. Small streams with names like Little Alder Creek, Lime Spring Branch, Dead Man Run … names that fairly screamed I AM FULL OF TROUT… all these places and more would now be accessible to us.

I began to subscribe to off-road magazines with cover photos of Jeeps, Broncos, and Land Cruisers high in the air, bouncing at high speeds off huge boulders. I could never get enough of those photos of off-road trucks with huge, aggressive tires, roll bars, and jerry cans of extra gasoline strapped to the rear.

I sent away to state game and fish departments for maps, brochures about National Forests, anything I could find that would enlarge our list of remote fishing spots. Doc and I studied them for hours, looking for exotic, hard-to-reach lakes and streams that would be ideal for day trips. We needed places where we could leave early in the morning, arrive at the chosen lake or stream, fish for several hours, then return in time for dinner. This was after all a family vacation. No sense unnecessarily antagonizing the women folk, who would be left all day to care for the children.

One of the many things I loved about my father-in-law was that he had somehow hung onto that boyish quality that most sixty-five year olds have long sense lost. I marveled at how a man thirty years my senior could get as excited as a small boy.

After much discussion we chose a small body of water with the enticing name of Lost Lake. The name reverberated through our fish brains like a number ten Royal Coachman being snapped off on a bad back cast. Lost Lake appeared to nestle snugly in a small meadow between two ten thousand foot peaks. The lake apparently covered about twenty acres and was just remote enough to make it interesting. Actually it wasn’t “off road” in the strictest sense. According to the legend on the Forest Service map we would leave the highway a few miles from our guest ranch and travel steeply up-hill about fifteen miles on a winding solid black line which indicated a gravel road. The solid black line would then become a dotted line indicating a Jeep trail. In other words there would be no one there who DIDN’T HAVE FOUR WHEEL DRIVE! Or maybe a horse.

Giddy with anticipation, we got up early the next morning, packed our tackle and lunch and headed for the high country. On the way we discussed our plan of attack. The trout in Lost Lake, probably native cutthroats or brookies, would be very shy, having never seen a human before. We would have to stop and rig up quite a ways from the water, then crawl on our bellies through the grass and, without getting too close, lob our flys onto the water, then wait for the unsuspecting trout to fight each other to see who could reach the tasty morsel first. We should also keep our eyes peeled for bears and the occasional mountain lion.

Our excitement grew as the road turned to gravel. We rolled the windows down so we could smell the cool mountain air. As we approached the fifteen-mile mark I checked to see if I knew how to engage 4WD as I had never actually done it before. Doc began to think aloud about which fly we should try first, a hopper pattern or a Rio Grand King.

Fifteen miles of gravel road came and went… and we were still on gravel. “So what?” I thought. The fifteen-mile distance was only an approximation. We’d be hitting that Jeep trail any minute. Probably just around the next hairpin curve.

I glanced at the odometer. “We’ve been on gravel for twenty-five miles now”, I said. Doc puzzled over the map in silence as we rounded one more curve and ascended higher and higher into the mountains, the smooth gravel road lined on both sides by tall pines and aspens. Something didn’t seem right.

The exact moment when you learn your plans have gone awry is not always apparent. Sometimes it creeps up on you. But not this time. A little girl, no more than ten years old, came roaring around the next curve toward us on a tiny motor scooter, her blond ponytail flying out behind her. She waved as she sped downhill past us and we rounded the curve and saw, for the first time, Lost Lake.

“Check the map again”, said Doc. “Maybe this isn’t it”.

I stopped the Bronco and grabbed the map off the console and stared at it.

“It’s gotta be”, I said. “But what happened to the Jeep trail? We could have driven up here in your Buick!”

A wooden Forest Service sign near the shore confirmed the bad news. This was, unfortunately, Lost Lake.

The lake was indeed nestled between two high peaks. And the scenery was beautiful. But the near side was lined with motor homes and camper trailers, some apparently pulled by low-slung family sedans. Fords, Chevvies, and Caddies. Someone had set up a net and two families were playing a heated game of badminton. The metallic clang of horseshoes hitting a post could be heard above the sound of several boom boxes in noisy competition with one another. Small children floated and splashed on inner tubes and colorful plastic rafts near the shore. Senior citizens rested in aluminum lawn chairs along the bank. Some of them dozed or read newspapers, their casting rods propped in forked sticks in front of them. Another child raced past us on a motor scooter and several boys zoomed about on bicycles. A toddler stood in a playpen as his mom sipped a can of beer and rigged up a heavy casting rod with prepared trout bait on a treble hook. I looked down at the nearby shore and saw one small dead rainbow trout, floating belly-up in the water, impaled on a large metal stringer secured to a tackle box.

The far shore of Lost Lake was steeper than this side but only slightly less congested. The newly graveled road completely encircled the lake and campgrounds full of happy campers were marked with neat wooden signs. One man appeared to be changing the oil in his Plymouth. A launching ramp at the far end was crowded with boats and trailers, some just now launching, others coming out. Several fishermen in boats appeared to be dozing on the water’s surface.

A green Fish and Game department pick-up rolled slowly toward us on the gravel road, stirring up a white cloud of caliche dust. The game warden was coming from the launching ramp where he had apparently been checking licenses and bag limits. He pulled his truck along side my Bronco.

“Why so glum, Fellas?” he asked, giving us a friendly smile. “It’s a great day to be out and about.”

I showed him our map and asked him about the Jeep trail.

“Oh, that”, he said, handing the map back to me. That’s the old 1963 map. He reached into the glove compartment and handed us a crisp, neatly folded new one.

“Take this one”, he offered. “This road was graveled clear to the lake two years ago. The county grades it and re-gravels it often because as you can see it gets a lot of traffic.” He opened the pick-up door, got out and leaned against the Bronco fender.

“If you plan to fish I’ll check your licenses if you don’t mind”.

Doc and I looked at one another. We had fished together long enough to read each other’s minds.

“Nope”, I said. “I think we’ll just try to get in on the badminton game.”

“Or maybe pitch some horse shoes”, added Doc.

Trout fishing on the Yellowstone River

The first thing you’ll notice about these fishing trip photos is that there are no photos of fish. There’s a reason for that. Few fish were caught. Just a few dinks and a couple of whitefish, which are, to the trout fisherman, what coots are to duck hunters.

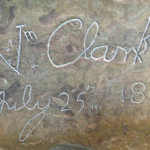

While attending the recent OWAA conference in Billings, Montana Brent Frazee and I took July 18th off to float the Yellowstone River. While waiting for our guide to get the boat into the water we noticed a sign informing us that William Clark and party had camped on this very spot July 17th, 1806. Just missed it by 210 years and one day! Sort of gave me goose bumps.

The Yellowstone has not been channeled into a ditch for barge traffic and probably looks pretty much as it did when William Clark, Sacagawea, her husband Toussaint Charbonneau, their little boy Jean Baptiste and the rest of the crowd traversed it in 1806.

You don’t need a lot of fish to enjoy a day like this.

The White-hot White River

Two days on the White River with outfitter/philosopher Miles Riley is what Arkansas trout fishing is all about.

We put in Wednesday morning at Rim Shoal and floated down past Shoestring Shoal to Riley’s Station where the Buffalo River meets the White, catching rainbows and a few cutthroats all the way. I don’t count fish but we must have boated and released at least two dozen.

Tandem rigs with pink San Juan worms, #20 bead head Prince nymphs, (pardon me…the nymph formerly known as Prince), or black #18 zebra midges worked all morning.

We found some shade and ate our shore lunch (‘cause we shore were hungry), then continued down river. The fish didn’t mind the 90-degree midday heat and the bite stayed good all afternoon. We called it quits at 4PM while I still had enough energy to drive back to Mountain Home.

Next day we motored upstream past towering bluffs on the left and stopped at Buffalo Shoal where we stayed all day. With action like this, why leave? We added something new to the arsenal: a midge developed by Steve Hegstrom called a Scarlett O’Hare. With this and the San Juan worm I proceeded to boat and release about 40 or 50 rainbows and cutts. The Hegstrom nymph was getting pretty ragged by mid afternoon so we traded it for a little gray bead head scud – Miles just called it his Guide fly – and continued to catch trout including several measuring between fifteen and seventeen inches.

On one cast I hooked and landed a cutt and a rainbow, one on each fly. Then several casts later it happened again but this time one fish threw the hook before being netted.

It’s hard to beat trout fishing like this. If you want to go, contact Miles or Michelle at http://www.rileysstation.com .

Colorado trout fishing in the 1950s

This story was first published in the August 2008 issue of Wyoming Wildlife under the title Trout Tourist.

“I’m just not going to fish like that!” yelled Doc, my father-in-law, as he stomped back into our rented summer cabin. He hung his fiberglass fly rod on two nails driven into the plywood wall, hurled himself into a chair, and started peeling off his hip boots.

“What’s wrong?” I asked innocently. I was new to trout fishing and didn’t understand stream protocol.

“What’s WRONG?!”, he roared, sending one hip boot skidding across the linoleum floor. “Some son of a bitch got in the water not two hundred yards from me! I’ll be damned if I’ll drive all the way out here to fish right next to some inconsiderate bastard!”

The clear mountain air was blue with swear words as he shuffled a deck of cards and started dealing a game of solitaire, slapping the cards violently onto the old wooden table.

That was 1958, my first year of marriage to his daughter and my first trout fishing trip. Since then I’ve enjoyed many years with the daughter and so many enjoyable days with her father on western trout streams that I can’t count them all. But I have to tell you, there have been a lot of changes since the ‘50s, some beneficial, some not.

Our equipment today is vastly superior to what was available then and we have a much greater variety of goodies from which to choose. Back then we used automatic fly reels. Mine fit horizontally against the reel seat and was filled with level fly line. In those days letters instead of numbers designated line size. A double taper might be HCH, a level line might be simply C or whatever. When I wanted to reel line in I pressed a protruding lever with my little finger and the spool whirred inside its green aluminum case, sucking in line like you’d suck a long string of spaghetti into your mouth.

Graphite fly rods might have been available somewhere but I didn’t see my first one until the ‘70s or ‘80s. We knew bamboo rods existed but we thought they were only for rich people. In 1958 if anyone had told me I would someday pay over $400 for a fly rod, $250 for a reel, and $60 for a fly line I would have laughed. Our rods were fiberglass, had names like Shakespeare and South Bend, and they served us quite well. Mine was all shiny and new in 1958 but Doc’s had been around a while and some of the guides were held on with black electrician’s tape. To say the man was not an equipment freak is an understatement.

The only flies we used were Rio Grande Kings, Royal Coachmen, and something called a Gray Hackle Yellow. In fact we didn’t even know about fly shops. We bought our flies at the hardware store, right next to the shovels and pick axes. The flies were all “snelled”, which meant they had a 3” piece of what appeared to be fifteen-pound test monofilament tied to the eye, with a big loop on the other end. One wall of the hardware store featured paper tracings of huge trout that had been hauled out of the surrounding waters. The name of the angler, trout’s weight and fly pattern, lure, or bait on which it was taken was written inside the outline of the fish. Doc and I would stare at those lunkers and hope that someday we would add a tracing of our own to the wall, but the biggest fish of the trip for us was always a thirteen or fourteen incher, flopping in the cabin sink and rapidly losing its color. We later learned that many of those “wall fish” were caught by local fishermen in the spring before runoff. We tourists were left to thrash the warmer July and August water for the little ten to fourteen inchers.

I didn’t own a fishing vest until much later. Besides rod and reel my equipment consisted of an old army gas mask bag for the few flies I carried, a pair of long-nosed pliers, a pocketknife, and an aluminum-frame net with an elastic cord. Dry flies as opposed to wet flies? Tapered leaders? Get serious! We tied straight sections of monofilament – usually the same six-pound test we’d been using for crappie – onto the looped end of the snell and started fishing. As long as the fly floated it was a dry fly. When it sank it became a wet fly. The trout didn’t seem to care and neither did we.

And yes, we ate some of the trout we caught. We stayed in the cabin ten days, tried to have a fresh trout dinner once or twice, and we usually managed to take home a possession limit. We never violated the regulations and Doc was proficient enough to release many more trout than he kept. I, on the other hand, was so proud of myself when I managed to actually catch a limit that I would put them on wet grass in my “creel” to keep them fresh while I took them around to show people in the other cabins. It was only after I became a more efficient predator that I discovered the joys of catch and release.

That first year my attempts at trout fishing were bumbling at best. I wore a borrowed pair of leaky stocking foot chest waders and my “wading boots” were high-top Ked sneakers. We didn’t know about felt soles yet, so I slipped and fell in the river a lot. However, to my surprise, when I kept my fly out of the trees and got it into the water I found I could occasionally bag a few small brownies and rainbows.

Years later a photograph of the opening day crowd at a popular Missouri trout park appeared in a national magazine. In the photo fishermen were literally lined up shoulder-to-shoulder waiting for a siren to blow signaling the start of trout season. I showed the photo to Doc and he thought it was a joke.

“You’re kidding me,” he said, staring in disbelief at the photo. “Nobody would fish like that.” I didn’t have the heart to tell him it was true.

Eventually Doc and I started fishing the Rio Grande twice a year, the second trip coming in the fall with a small group of other men. The weather was crisp, the aspens were bright yellow, and the trout were still reasonably cooperative.

Doc was usually head cook on these outings, and he said that after he got too old to fish he still wanted to come out with the group to cook for us and play cards. But a strange thing happened. As he grew older his wading and fishing skills stayed fairly sharp but his cooking deteriorated to the point where he had to be gently persuaded to let someone else take over most of the kitchen duties.

As I look back on fifty years of fishing Colorado I wouldn’t trade my experiences for anything. Oh, I could do without some of the burnt biscuits, the scorched trout, and the dunkings I took while balanced in rubber soled boots on slippery rocks. But over all they are some of the most enjoyable memories of my life and I can hardly wait to get back out there and make some more.

Timber Hills Lakes

Had a great two days at Timber Hills Lakes near Mapleton, KS with the Kansas Outdoor Writers. These folks really treated us nice and I’m looking forward to going back there as soon as possible.

Lots of lakes and ponds full of bass, crappie, bluegill and even trout. And they have little two-man (or woman) pontoon boats with electric motors you can use. Also you can turkey hunt…and I’m probably leaving something out…like deer hunting. And they have a well-stocked bar! And nice, comfortable cabins.

I stood in one place and caught this big bass, several smaller bass, two rainbow trout and several crappie, all on one fly (a gray & white Clouser).

It doesn’t get any better than this. Check it out at http://www.timberhillslake.com .

Crane Creek

Crane Creek.

I had heard about it long before I was fortunate enough to fish it. Finally in 1999 a Springfield, Missouri DARE cop named Joe Curry and I spent several hours on this beautiful little stream near Springfield. We were accompanied by a local resident of Crane, MO, a fly tier whose name escapes me.

Crane Creek is not stocked and is strictly catch-and-release fly fishing. The trout are stream-bred McCloud rainbows. The fly tier wore a side arm because he said we might run into some “subhuman bait-dunking redneck scum” not observing the catch and release regulations who might become unruly when chastised. Luckily we did not have to shoot our way out of Crane Creek and did manage to catch a few beautiful little McCloud rainbows.

My friend and fellow http://www.heartofamericaflyfishers.com member Terry Robbins recently fished Crane. He did not report any encounters with belligerent bait dunkers but did manage to catch a 22” rainbow, the largest trout I’ve ever heard of to come out of this tiny stream.

Maggie

When I take Maggie to the farm I throw training dummies in the water for her and she chases the ATV (or I chase her) over most of our 200 acres. When we get home she follows me around the house, room to room, until I take the whistle from around my neck and hang it on the hook in my studio, remove my farm shoes and my old blue work shirt. Only then does she realize the fun is over for another day and she can safely collapse into her road kill imitation without missing out on something.